Edgar Degas

Edgar Degas, in full Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas, De Gas later spelled Degas, (born July 19, 1834, Paris, France—died September 27, 1917, Paris), French painter, sculptor, and printmaker who was prominent in the Impressionist group and widely celebrated for his images of Parisian life. Degas’s principal subject was the human—especially the female—figure, which he explored in works ranging from the sombre portraits of his early years to the studies of laundresses, cabaret singers, milliners, and prostitutes of his Impressionist period. Ballet dancers and women at their toilette would preoccupy him throughout his career. Degas was the only Impressionist to truly bridge the gap between traditional academic art and the radical movements of the early 20th century, a restless innovator who often set the pace for his younger colleagues. Acknowledged as one of the finest draftsmen of his age, Degas experimented with a wide variety of media, including oil, pastel, gouache, etching, lithography, monotype, wax modeling, and photography. In his last decades, both his subject matter and technique became simplified, resulting in a new art of vivid colour and expressive form, and in long sequences of closely linked compositions. Once marginalized as a “painter of dancers,” Degas is now counted among the most complex and innovative figures of his generation, credited with influencing Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and many of the leading figurative artists of the 20th century.

Beginnings

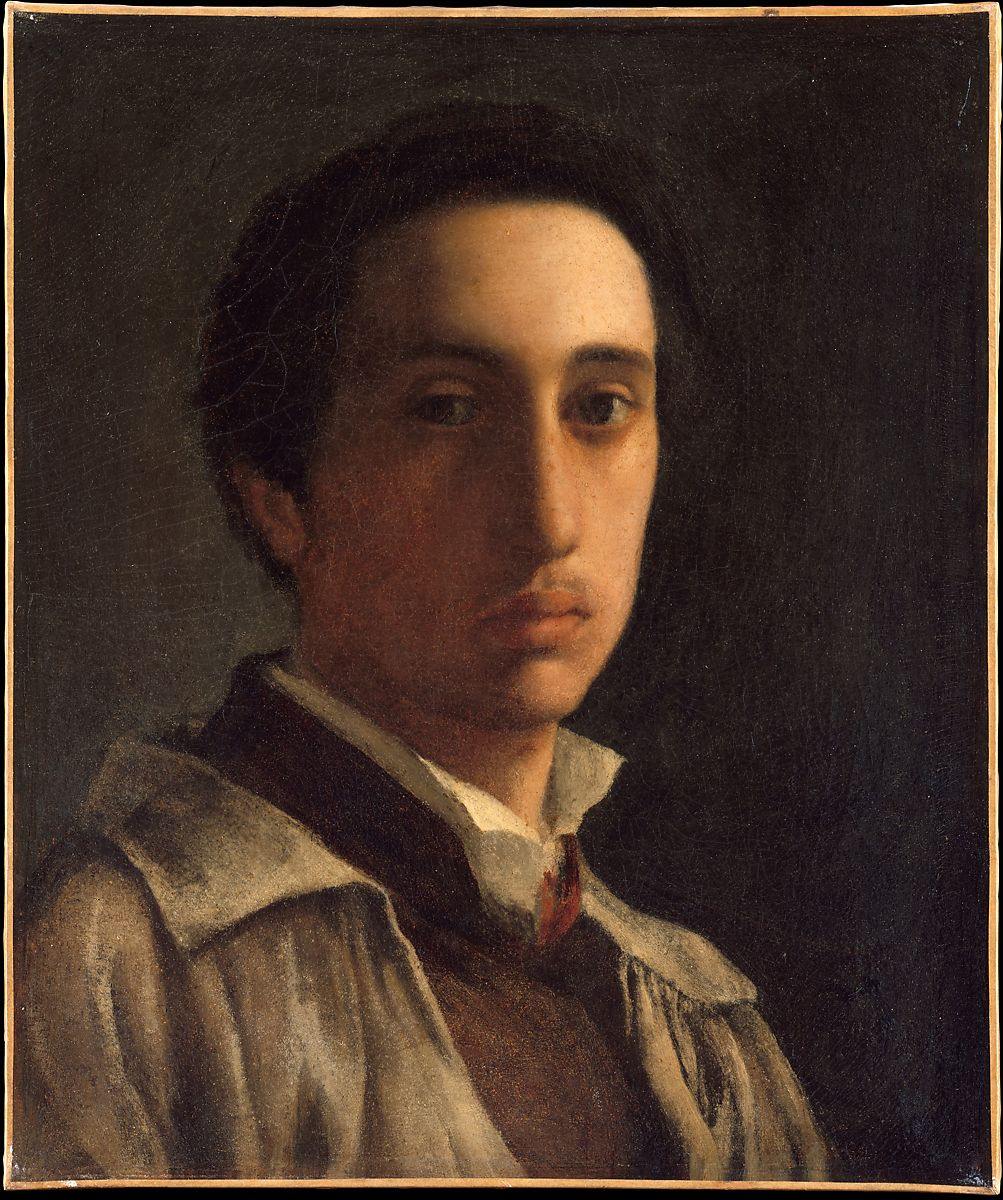

Born in Paris just south of Montmartre, Degas always remained a proud Parisian, living and working in the same area of the city throughout his career. Music featured prominently in the Degas home, where the artist’s mother sang opera arias and his father arranged occasional recitals, one of which is represented in Degas’s painting of 1872, Lorenzo Pagans and Auguste De Gas. The artist’s mother died when he was 13 years old, leaving three sons and two daughters to be brought up by his father, a banker by profession. Degas’s father helped to develop his son’s interest in painting and in 1855 encouraged him to register at the École des Beaux-Arts under the supervision of Louis Lamothe, a minor follower of J.-A.-D. Ingres. Surviving works from that period show Degas’s aptitude for drawing and his attention to the historical precedents he viewed in the Louvre. He also began his first solemn explorations of the self-portrait.

In 1856 Degas surprisingly abandoned his studies in Paris, using his father’s funds to embark on a three-year period of travel and study in Italy, where he immersed himself in the painting and sculpture of antiquity, the trecento, and the Renaissance. Staying first with relatives in Naples, he later worked in Rome and Florence, filling notebooks with sketches of faces, historic buildings, and the landscape, and with hundreds of rapid pencil copies from frescoes and oil paintings he admired. Among these were copies after Giotto, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Titian, artists who were to echo through his compositions for decades; the inclusion of less-expected works, however, such as those by Sir Anthony van Dyck and Frans Snyders, hinted at wider interests. The same sketchbooks include written notes and reflections, as well as drafts for his own figure-based paintings in a variety of eclectic styles. Together they suggest a literate and serious young artist with high ambitions, but one who still lacked direction.

Colour and line

From his beginnings, Degas seemed equally attracted to the severity of line and to the sensuous delights of colour, echoing a historic tension that was still much debated in his time. In Italy he consciously modeled some drawings on the linear restraint of the Florentine masters, such as Michelangelo, Characteristically, the young Degas developed a near reverence for Ingres, the 19th-century champion of Classical line, while almost guiltily imitating Eugène Delacroix, who was the leading proponent of lyrical colour in the century and considered to be Ingres’s antithesis. Many of the pictures of Degas’s maturity grew out of a confrontation between these impulses, which arguably found resolution in the vigorously drawn and brilliantly coloured pastels of his later years.

Returning to Paris in April 1859, Degas attempted to launch himself through the established art-world channels of the day, though with little success. He painted large portraits of family members and grandiose, historically inspired canvases such as The Daughter of Jephthah (1859–60) and Semiramis Building Babylon (1861), intending to submit them to the annual state-sponsored Salon.

Perhaps humbled by his exposure to the Italian masters, Degas scraped down and reworked parts of his own canvases, initiating a habit of technical self-criticism that was to last a lifetime. In 1865 his more simply executed Scene of War in the Middle Ages was accepted by the Salon jury, but it remained almost unnoticed in the thronged exhibition halls.

Realism and Impressionism

Degas’s transition to modern subject matter, evident in Scene from the Steeplechase, was a long and gradual one, not an overnight conversion. Before he left Italy, he had made drawings of street characters and paintings of fashionable horse-riders, but always on a small scale. In Paris in the early 1860s, his pictures of French racing events broke new ground both for their decidedly contemporary subject matter and for their surprising viewpoints and bold colours, which preceded the canvases of similar scenes by his renowned contemporary Édouard Manet. Degas’s portraits, too, at this time became less remote and more actively engaged with the top-hatted, restless world in which he lived. When he met Manet about 1862, Degas developed an affectionate but pointed rivalry with the slightly older man and soon shared something of Manet’s oppositional stance toward the artistic establishment and its traditional subject matter. Degas’s notebooks from these years teem with contrary possibilities for the direction of his art, as sketches of the countryside follow glimpses of theatrical performances, and studies from objects in the Louvre are interspersed among topical caricatures. After mid-decade he abandoned historical themes, sending a portrait of a current ballet star at the Paris Opéra, Eugénie Fiocre, to the Salon of 1868; he would soon reject such official exhibitions altogether.

By 1870 Degas was a familiar figure in independent art circles in Paris, at home with Realists such as James Tissot and Henri Fantin-Latour, acquainted with the vanguard critics Edmond Duranty and Champfleury, and involved as an occasional but forceful presence at the Café Guérbois, where avant-garde artists such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Claude Monet would also meet. He was famously opinionated, supporting these radical artists’ shared belief that painting should engage with the sights and subjects of the modern world. As part of his own process of engaging with modernity, he self-consciously aligned himself with Realist novelists such as Émile Zola and Edmond and Jules Goncourt, drafting illustrations for their novels and briefly adopting a similar social descriptiveness.

Like most of the future Impressionists, Degas lightened his palette and adopted more abrupt, simplified compositions during this period, partly under the influence of Japanese prints, which were very popular among contemporary artists. But, unlike his colleagues, who were experimenting with painting en plein-air, Degas affected disdain toward the improvised outdoor landscape studies for which many of the Impressionists became known. Although he clung to the habit of drawing in preparation for his pictures and insisted on working in the studio rather than outdoors, in 1869 Degas did experiment in private with a series of pastel landscapes executed on the Normandy coast. While he is not generally associated with them, he would turn to other rural subjects on several occasions in later life. Degas’s advancing self-confidence at this date, boosted by the first signs of public recognition, is palpable in his letters and the range of his technical accomplishment.

The early 1870s were critical in defining Degas’s personal and artistic trajectory, as they were for the other artists who would be known as the Impressionists. Between 1870 and 1873 he painted a pioneering group of ballet rehearsal and performance scenes, such as his Dance Class of 1871, finding eager buyers for many of them and soon becoming identified with their theme. The dance allowed Degas to test his skills in a daring new context: the world of the Paris Opéra was surrounded by sexual intrigue as well as high glamour and had previously been the province of popular illustrators. Degas built on his knowledge of past art, but he cleverly directed it at audiences of his own day in his choice of subject matter; his views of backstage activity are conspicuously casual and occasionally scurrilous. In 1874 he was one of the leading organizers of the first Impressionist exhibition (which he called “a salon of Realists”), showing his signature repertoire of dancers, horse races, and women ironing.

Degas left in 1872 for a protracted visit to his relatives in New Orleans, where he pursued his experiments in family portraiture in spectacular works such as the Cotton Office at New Orleans (1873). Over this same period he began to describe a deterioration in his eyesight, complaining of intolerance to bright light and wondering if he might soon be blind.

The pictures Degas showed at the series of eight Impressionist exhibitions, held between 1874 and 1886, revealed him at his most inventive. Whereas the paintings of Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, Paul Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Camille Pissarro, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir were largely concerned with the landscape or with figures of rural toil and urban glamour, Degas specialized in startling and enigmatic scenes of Parisian life. Visitors were frequently disconcerted by his images of popular entertainment or back-street squalor, depicted with a sharp eye for the topical gesture and heightened by a radical use of perspective, which embodied the extreme viewpoints of a newly mobile society. Already famed for his dry humour, Degas seemed to tease his viewers by opting for ambiguity, revealing a glamorous nightclub singer in all her awkwardness, while elevating a tired laundress to near-Classical grandeur. Degas was seen as the leader of a more traditionally skilled faction within the group, and his pictures were sought out by collectors. Critics approvingly pointed out that his work was grounded in a knowledge of the Old Masters and a firm line, qualities they found lacking in some of Degas’s peers.

A versatile technician

For much of his long working life, Degas was attracted to the pleasures and difficulties of the artist’s materials. His drawings include examples in pen, ink, pencil, chalk, pastel, charcoal, and oil on paper, often in combination with each other, while his paintings were carried out in watercolour, gouache, distemper, metallic pigments, and oils, on surfaces including card, silk, ceramic, tile, and wood panel, as well as widely varied textures of canvas. There was something contradictory about much of this activity: Degas invoked the techniques of the Old Masters while creating anarchic methods of his own. He effectively developed the black-and-white monotype as an independent medium, for example, sometimes with an added layer of pastel or gouache, as in Dancer with a Bouquet Bowing (1877). The results can be exhilarating, notably when the effects of light and texture are subtly expressive of the chosen subject, but he soon tired of the technique. The late 1870s marked the height of Degas’s graphic experimentation, after which he moved away from printmaking to concentrate on enriching his use of pastel. Between 1890 and 1892 he briefly returned to monotype, perfecting a new colour procedure in a dazzling series of landscapes, many—like Wheat Field and Green Hill—with pastel embellishments.

By the early 1880s the variety of Degas’s exhibited art seemed endless, encompassing portraits and theatre scenes, pastels of women at their toilette and of notorious criminals, and series of drawings and prints. During this period Degas began to experiment with making pictures as charcoal drawings on tracing paper and retracing them several times before adding pastel to produce a “family” of related compositions, analogous to the series paintings of Monet. Such sequences were deeply challenging artistic exercises, allowing him to move beyond subject matter and to manipulate the finest nuance of gesture or detail, while seeming to elevate the fundamentals of picture-making—colour, form, and composition—to a newly independent level. For some years Degas had also been quietly exploring the medium of sculpture, using wax and other materials to make modest statuettes of horses and a group of figures that culminated in the tantalizingly lifelike wax sculpture, The Little Dancer Aged 14 (1878–81). Shown at the Impressionist exhibition of 1881, this work carried the possibilities of visual realism to new extremes by incorporating an actual, reduced-scale tutu, ballet slippers, a human-hair wig, and a silk ribbon.

Final years

In 1884 Degas reached the age of 50 and confessed to his friends that he felt some disillusionment about his career. He abandoned many of the topical themes of the 1870s—the café-concerts, shop scenes, and brothels, for example—and replaced them with a new phase of concentration on the human figure in intimate, if more indistinct, settings. After a controversial sequence of pastels in the 1886 Impressionist exhibition, which showed women bathing and drying themselves indoors and in the open air, Degas produced hundreds of obsessive studies of the nude female form on paper and canvas or in wax and clay.

The second great subject of Degas’s later years was the dancer, now infrequently on stage or in compromising situations, but rather more often waiting in the wings. He hired models to pose in his studio for both his ballet and bathing scenes, often freely improvising his settings or utilizing familiar props. Though they never became abstract in any sense that Degas would have understood, the works of this period moved significantly away from the urban context that had formerly inspired him.

In such works Degas seemed to be confronting the beginnings of a new art, where documentary description counts for little and the preoccupations with structure and expression of the early 20th century are spelled out. As in his nude studies, his pastels of dancers were sometimes lightly tinted over an energetic charcoal drawing, or were otherwise densely built up in crusty layers of brilliant, unnatural hue. The old dialogue between colour and line continued, but in an emphatically modern idiom. A fascination with varied techniques haunted Degas to the end, resurfacing in dramatic and occasionally bizarre late canvases that involved finger-painting, glazes of contrasting colour, and heavily impastoed surfaces.

It was not until after Degas’s death in 1917, however, that the wealth of his output was revealed in a succession of vast public sales in the war-shocked Paris of 1918 and 1919. Thousands of his previously unexhibited works on paper and canvas were sold, and some of the later, less naturalistic examples distressed even his most loyal admirers. Certain aspects of his achievement gained prominence for the first time, principally the wide range of his printmaking. Also surprising was the extent of his collection of pictures by El Greco, Ingres, Delacroix, Manet, Gauguin, and Cézanne. In the early 1920s, when the first series of posthumous bronze casts were unveiled in Europe and the United States, Degas’s sculpture provided a further revelation to the art world.

Legacy of Edgar Degas

Degas’s greatness is summarized in his ability to explore the language of art—its technical and tactile complexity, its refinement as well as its implicit energy—to a more extreme degree than any of his contemporaries, yet without losing sight of his subject of the human animal in its most public and private moments. He combined a Romantic sensibility with a Classical command of his means, fusing sensuality with unsparing observation and an insistence on visual structure. More than any of the other Impressionists, Degas’s art has long been simplified or over-categorized: in reality, the evolution from the gloomy academicism of his youth to the full-blooded social realism of the 1870s, and then to the pyrotechnical, defiant breadth of his last two- and three-dimensional work, is one of the most awe-inspiring of the modern period. In a single lifetime, Degas abandoned the certainties of a state-controlled, historical culture for an art of individual crisis, even approaching the nihilism of the following generation.

Degas’s reputation has followed an unusual trajectory, rising steeply in his maturity but suffering from the angry retreat of his old age, and from the preference for nonfigurative modes in the new century. Though respected in subsequent decades, he was sidelined by formalist criticism and relegated too often to the role of mere social commentator. The 1960s and ’70s saw the beginnings of a major reevaluation of Degas’s significance, with specialist publications on his portraits, drawings, prints, monotypes, notebooks, and sculpture, and a growing wave of popular exhibitions. His imagery became a battleground for feminist critics, who centred on the artist’s alleged misogyny and the perceived prurience of his brothel and backstage scenes. More recently, the self-consciously elusive quality of much of Degas’s depiction has been increasingly acknowledged, as well as his underestimated shift away from topicality in later years. Such debates and discoveries continue to attract vast crowds and to stimulate curators, academics, and practicing artists, suggesting that Degas’s full stature has yet to be fully measured.

Source: Wikipedia